Humane Genetics Curriculum

Copyright owners: Brian Donovan, Philip Keck, Robbee Wedow, Monica Weindling, Andy Brubaker

Authors: Brian Donovan, Rob Semmens, Phillip Keck, Elizabeth Brimhall, K.C. Busch, Monica Weindling, Alex Duncan, Brae Salazar, Paul Strode, Jean Flanagan, Andy Brubaker, Awais Syed, Dennis Lee, Jamie Amemiya, Robbee Wedow, David Angwenyi, Kirsten Milks, and Stefanie Ribecca.

Project collaborators: Yeongmi Jeong, Kathryn Malerbi

COPYRIGHT STATEMENTS

Use of these materials for instructional purposes, and not for financial gain, is allowed under Creative Commons license CC-BY-NC-ND. Using these materials in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence models and technologies is strictly prohibited.

Throughout these materials, various images are used with or adapted with permission from published sources. These images are properly attributed and/or cited in the materials below, and those attributions and/or citations should also be carried over for any instructional uses or adaptations of these materials. In particular, we use or adapt with permission (under Creative Commons license CC-BY-NC-ND) several images from our own published work (Donovan et. al., 2019 and Malerbi et. al, Forthcoming).

Team

Brian Donovan, PhD

Creator of humane genetics and principal investigator of the research behind it

Email | ORCID | Google Scholar

Monica Weindling

Curriculum co-developer, professional development co-facilitator, and research activities manager

Andy Brubaker

Curriculum co-developer and professional development co-facilitator

Robbee Wedow, PhD

Co-Investigator

Email | ORCID | Google Scholar

Curriculum Goals

The goals of this unit are to reduce students’ belief in racial genetic essentialism and improve their ability to refute essentialist arguments by increasing their understanding of 1) human population genetics, 2) multifactorial causation of complex human traits, and 3) how scientists reason with evidence and avoid reasoning errors.

Curriculum Overview

The humane genomics curriculum will help your students understand patterns of human genetic variation and the multifactorial basis of complex human traits. When students develop these understandings, research shows, they become less likely to endorse prejudiced views about racial difference.

Our curriculum materials are the only ones clinically proven through randomized trials to robustly and effectively reduce scientifically inaccurate beliefs in genetic essentialism in students.

Curriculum Anchoring Phenomenon

Unit Phenomenon: White people are overrepresented in STEM and underrepresented in the NFL, and Black people are underrepresented in STEM and overrepresented in the NFL.

Unit Question: What are the causes of racial disparities in STEM and the NFL, and how can we be sure our explanation is accurate?

Chapter 1 (Lessons 1-5)

Chapter 1 Question: What is an accurate understanding of genetic differences within and between racial groups?

Chapter 1 Big Idea: Most genetic variation occurs within racial groups, and there is very little genetic variation between racial groups.

Chapter 2 (Lessons 6-9)

Chapter 2 Question: What is the best explanation (genes or environment) for observed differences between racial groups?

Chapter 2 Big Idea: Environment is most likely a better explanation for racial disparities than genes because there is evidence that racial groups experience different environments, and when environments change, differences between races also change.

Alignment with the Next Generation Science Standards

Details about NGSS alignment are provided beginning on page 6 of the teacher materials (linked below).

Key Instructional Frameworks

The Humane Genetics curriculum incorporates the following instructional frameworks to enhance student sensemaking and curriculum coherence. These summaries are detailed further in Malerbi, et al. (forthcoming).

-

As outlined in the Next Generation Science Standards, the purpose of utilizing an anchoring phenomenon is to elicit initial student ideas about the causes of an observed phenomenon so students can then use evidence to evaluate the accuracy of these ideas over the course of a unit. This helps students arrive at an evidence-supported consensus explanation for the phenomenon by the unit’s end (“Using Phenomena in NGSS-Designed Lessons and Units”, 2016).

-

This narrative uses fictional characters to tell a story of overcoming science denial (Darner, 2019). When students encounter information that runs counter to their current worldview, they are less likely to engage in analyzing that evidence. This can be problematic – if a student’s current worldview does not align with the available scientific evidence, this student is unlikely to engage in the evidence analysis needed to align their view with the accepted scientific consensus view. Evidence-laden narratives can be used to encourage willingness to engage in evidence analysis and prevent denial of science ideas among students by using conversations between fictional characters to model for students how to change one’s mind based on evidence (Darner, 2019). This curriculum utilizes two characters, Robin and Taylor, to help students evaluate the accuracy of essentialist and non-essentialist ideas.

-

Contrasting cases helps students develop the requisite knowledge necessary to evaluate evidence (Schwartz & Bransford, 1998). Students are first presented with hypothetical data sets, and then compare these hypothetical data and highlight the distinct ways they vary. This process helps students develop the relevant prior knowledge they need to interpret the key elements of the actual data. Students then analyze the actual data using their new knowledge and explain what the actual data demonstrate.

-

HGL incorporates discussion scaffolds known as academically productive talk moves to support student discussions. These talk moves encourage all students to participate, and the role of the instructor is to “guide students in practicing new ways of talking, reasoning, and collaborating with one another” (Michaels & O’Connor, 2012). Students are encouraged to explain their thinking and support their ideas with evidence.

-

To help students synthesize the key ideas in this curriculum, HGL has students create and iteratively refine models that incorporate all the available evidence to explain the anchoring phenomenon. Students construct these models using model-based reasoning principles in which students create the simplest model that best incorporates all the evidence, a practice known as synthesis modeling (Shemwell et al., 2015). They then use these synthesis models at the end of the curriculum to construct an explanation for the anchoring phenomenon.

References for Instructional Scaffolds

Darner, R. (2019). How Can Educators Confront Science Denial? EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER, 48(4), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19849415

Michaels, S., & O’Connor, C. (2012). Talk Science Primer. TERC. https://pod-stem.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TalkScience_PrimerTERCPages1-6.pdf

Schwartz, D. L., & Bransford, J. D. (1998). A Time for Telling. Cognition and Instruction, 16(4), 475–522. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci1604_4

Shemwell, J. T., Chase, C. C., & Schwartz, D. L. (2015). Seeking the general explanation: A test of inductive activities for learning and transfer. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(1), 58–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21185

Using Phenomena in NGSS-Designed Lessons and Units. (2016, September). Next Generation Science Standards. https://www.nextgenscience.org/sites/default/files/Using%20Phenomena%20in%20NGSS.pdf

Related Curriculum Papers

Overview of the research behind this curriculum read:

Donovan, B. M. (2021). Ending Genetic Essentialism Through Genetics Education. Human Genetics and Genomics Advances, 3(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xhgg.2021.100058

Evidence in support of the efficacy of these materials:

Donovan, B. M., Semmens, R., Keck, P., Brimhall, E., Busch, K. C., Weindling, M., Duncan, A., Stuhlsatz, M., Bracey, Z. B., Bloom, M., Kowalski, S., & Salazar, B. (2019). Toward a more humane genetics education: Learning about the social and quantitative complexities of human genetic variation research could reduce racial bias in adolescent and adult populations. Science Education, 103(3), 529–560. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21506

Donovan, B. M., Weindling, M., Salazar, B., Duncan, A., Stuhlsatz, M., & Keck, P. (2020). Genomics literacy matters: Supporting the development of genomics literacy through genetics education could reduce the prevalence of genetic essentialism. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, tea.21670. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21670

Donovan, B. M., Weindling, M., Amemiya, J., Salazar, B., Lee, D., Syed, A., Stuhlsatz, M., & Snowden, J. (2024). Humane genomics education can reduce racism. Science, 383(6685), 818–822. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi7895

Evidence that the curriculum is effective across different instructional modalities, sexes, races/ethnicities, and worldviews:

Wedow, R., Jeong, Y., Thompson, K. N., Malerbi, K. F., Brubaker, A., Weindling, M., Lo, S. M., Amemiya, J., & Donovan, B. M. How and for whom can genetics education reduce beliefs in genetic essentialism? Human Genetics and Genomics Advances. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xhgg.2025.100548

Teacher Materials

The following link is for the comprehensive teacher materials for this unit. This document contains an overview of the unit, connections to aligned NGSS standards, and detailed instructions and guidance for implementing each lesson of this curriculum in your classroom.

Below it are further resources for helping teachers orient to and navigate the curriculum.

Lesson Materials

Below you will find the big idea, a link to the student materials, and a link to the slide decks for each lesson.

-

Science classes require students to engage in academically rigorous conversations to understand difficult concepts. In order to create an environment for students that is as safe as possible and facilitates academically productive conversations, it is important for teachers and students to agree upon behavioral norms they will follow when interacting with one another. In this lesson, the teacher and students will co-construct, agree upon, and practice these norms in groups to establish an environment that fosters productive academic conversations. We encourage teachers to implement this lesson toward the beginning of the year so students are skilled in using these norms by the time they reach the Humane Genetics unit.

-

In this lesson, students figure out: Racial disparities exist in representation in the NFL and STEM, and there are different possible explanations for why these disparities exist.

-

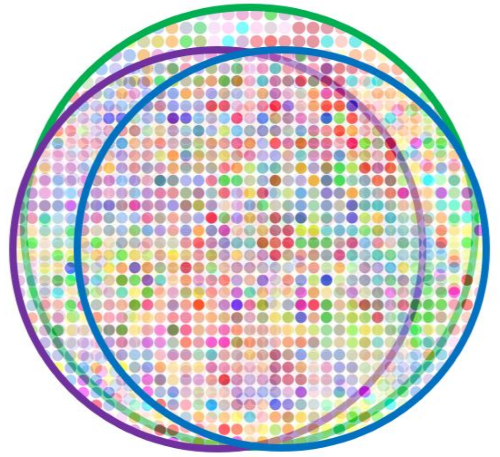

In this lesson, students figure out: There is genetic variation both within AND between racial groups. The amount of genetic variation within a racial group can be modeled by increasing or decreasing the size of a circle; the amount of genetic similarity between racial groups can be represented by the amount of overlap between circles.

-

In this lesson, students figure out: The amount of genetic variation within any racial group is large, the amount of shared within-group variation is large, and the amount of between-group variation is small.

-

In this lesson, students: Construct an accurate consensus model of human genetic variation that visually represents high within-group variation, high shared-within group variation, and low between-group variation.

-

In this lesson, students: Support an argument with evidence that most genetic variation occurs within racial groups and there is very little genetic variation between racial groups.

-

In this lesson, students figure out: An accurate causal model of human trait variation shows that the environment has a large effect, genetic factors a small effect, and unknown factors a moderate to large effect on human trait variation.

-

In this lesson, students figure out: There is evidence that environments differ between races in the US. When environments are more equal, disparities between racial groups are smaller.

-

In this lesson, students figure out: Genes can be a cause of variation within a group if all group members experience the same environment. But, because different races experience different environments, and because racial disparities change across environments, we should be skeptical of anyone who claims that racial disparities boil down to genes alone.

-

In this lesson, students figure out: Misinformation about racial disparities can be refuted with scientific evidence.